THE DANUBE

Introduction

Introduction Vidin

Between Vidin And Ruse

Ruse

Silistra

`Culture flows down the Danube to the Balkans and anarchy flows back up` goes a popular Bulgarian saying and, true or not, it underlines the importance of the Danube, Dunav in Bulgarian, as a major artery of communication and trade between Western Europe and the Balkans. It was not always so, the Ancient Greeks, the Macedonians and the Thracians saw the Danube as a barrier against the barbarian tribes of northern Europe and Romans, Byzantium, Bulgarians and Turks all fortified the southern bank against incursions from Central Europe. It was not until the 19th century that the river began to assume its importance as the trading route that it is today. Trade brought with it central European social customs, not perhaps opposed as much by the region`s Turkish governors as they would have done had they been closer to Constantinople. In consequence the Danube’s two major towns, Vidin and Ruse, developed a cosmopolitan and sophisticated society and even today they still have an air about them of fin-de-siecle culture that one does not find elsewhere in Bulgaria.

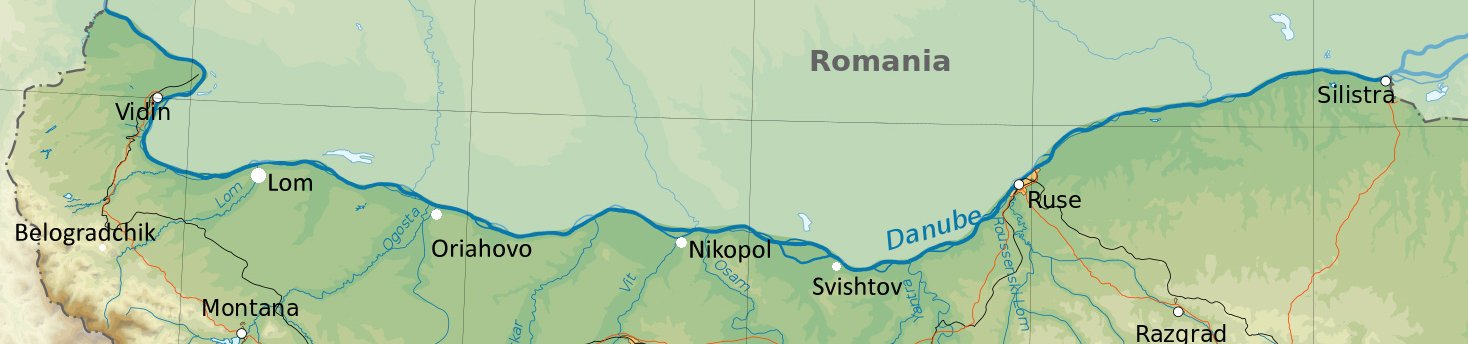

The Bulgarian bank of the Danube, its border with Romania, is mostly heavily wooded cliff in contrast to the marshes and reed beds of the low-lying northern bank and the river throughout its Bulgarian length is dotted with small islands, some of them visitable by boat. Hydrofoils and passenger boats used to run regularly between Vidin and Ruse and on to Silistra but stopped in 1992, although it is still possible by enquiring at local Tourist Information Offices or independent travel agents to find boats that run either part or all of the river.

VIDIN (ВИДИН)

Driving into Vidin it is difficult to get away from the fact that the town is one of the Danube`s major ports, the view from the south as the visitor approaches seems to consist entirely of cranes and blocks of flats but from that vantage point all these hide Vidin`s major attraction, the ancient fortress of Baba Vida (literally grandmother Vidin) which dominates the northern end of the town. Baba Vida has been down the centuries Vidin`s raison d`etre, guarding the country’s north-west approaches.

The Romans first fortified Vidin in the 3rd and 4th century BC, followed by Byzantium and in the 7th century the Bulgarians. Legend has it that the Bulgarian fortress was named after the daughter of a first Kingdom Tsar. For much of the Second Kingdom, isolated from the court at Turnovo, Vidin was almost an independent state and did briefly achieve full independence under Ivan Stratsimir in 1371 whose short rule was ended by the Turks in 1395. In 1396 Crusaders took the city but were beaten back by the Turks two years later. Four centuries later a Turkish Governor, Sultan Osman Pazavantoglu, carried on Vidin`s tradition of independence by rebelling against Sultan Selim III. He rebuilt the fort with the help of French engineers, supplied by Napoleon in the hope of gaining a toehold in the Balkans. Over the centuries Vidin has been first port of call for successive groups of refugees, Albanians, Kurds, Druses from Lebanon and Spanish Jews, some of whom were absorbed into the local population but in the 1860`s the Turks resettled a considerable number of Circassians between Vidin and Lom, refugees from the Russian Tsar and perhaps the most damaging of all the immigrant groups. In many villages they established a reign of terror, forcefully ousting villagers from their homes and in some cases clearing whole villages of the indigent population for their own use.

THE CITY

Baba Vida itself is best approached from the riverside park, which can be entered from the main square, Pl. Bdin (the city’s old name). The old fortress walls run along the seafront for almost a kilometre before they join the sturdy curtain walls and the deep moat of the fortress. Most of it dates from the 13th century, although substantial portions, including the towers, were rebuilt by the Turks. Inside there is an extensive network of courtyards, shielded by battlements guarded still by old cannon looking over the Danube and reconstructed seige engines and a battering ram. Part of the fort is given over to a museum and, in the summer, an open-air theatre staging folk-music performances. The walls continue north and west of the fort in a large semicircle through a modern housing estate and would have originally stretched back to the main square and the Stambul Kapia, or Istanbul Gate on its north side. The area that once was enclosed by the fortress walls is perhaps the most pleasant part of the city, in a quarter of 19th century houses the Osman Pazvantoglu Mosque stands out near the park with on one side an old Koranic library, now an art gallery. The town’s other attraction, near the main square is the Archaeological Museum, once the konak (the old Ottoman police station) and known universally as the konaka. Its collections are devoted mostly to the Roman period although also with a display of National Revival material. Its ethnographic collection is in Krastatata Kazarma (literally The Cross-Shaped Barracks) in the centre of the old town, with displays on 19 th century and early 20th century life in the Vidin region.

AROUND VIDIN

Some 60 kms. south of Vidin, the town of Belogradchik (Белоградчик - regular bus from Vidin) lies in one of the most spectacular rock formations in Europe. Covering 90km (36 ml), the weathered limestone has been formed into fantastic shapes, suggestive of castles, towers or mythical beasts, some over 153m./500ft. high. The rocks nearest the town have been a fortress since ancient times, guarding the entrance to the Belogradchik pass, once the main trading route between the Danube and the hinterland.

The town sits atop a small hill up which its main street climbs from the town square at the bottom. On the way it passes the town museum specialising in local ethnography and the Husein Pasha Mosque up to the gate of the citadel. (Open every day). From here three levels of occupation are evident, the top and oldest level is Bulgarian and the bottom two Ottoman. Climbing to the top level, through three gates one can see that the rocks form a perfect natural fortress which only needed some filling in of the gaps to become secure. The Turks used the citadel as a base from which to exert iron control over the local populace, at its most severe when dealing with the participants in a failed rebellion of 1850. The Turks captured many of the insurgents` leaders and imprisoned them in the fortress. Promising to release them they allowed them to file out through a low gate, at the other end of which, they were beheaded by a Turkish executioner as they emerged head bowed. By the outermost gate there is a monument to the dead. The rocks can also be approached from the town square from where a path leads through some of the more spectacular formations. In recent years threre have been concerts in the fortress during the summer months.

Another nearby geological spectacle is the Magura Cave (Magura Peshtera - open every day) near the village of Rabisha (bus from Belogradchik). The cave was inhabited since pre-history and the inhabitants have left rock paintings of a variety of figures - a giraffe, a woman, a bear and a man fighting an animal. The paintings were executed with paint made from bat droppings, which, interestingly has proved more resilient than the surrounding rock, many of them stand out from the rock face which has eroded around them. Guided tours of the caves, which extend about 1.5 miles into the hillside, take 90 minutes.

A winding road follows the river bank between Vidin and Ruse, sometimes detouring inland, connecting a myriad of little ports and villages and three main riverside towns. The countryside around is workaday land, mostly intensively cultivated, although Roman, Byzantine and Turkish remains abound, reflecting the river`s strategic importance down the centuries. Two of the towns have hotels, Lom and Svishtov and although it is feasible to travel by bus, a car makes the journey easier. Between Vidin and Lom (Лом), the road follows the wooded riverbank, the last 20 kms. or so a long unbroken cliff. Lom itself was the Roman settlement of Almus of which little remains today, although the Historical Museum displays a range of Roman finds and a collection of Bronze Age pottery. Today the town is a port rivalling Vidin and additionally renowned for the size of its watermelons, a regional delicacy.

From Lom the road leads on through Kozlodui (Козлодуй), known previously as the town where the poet Hristo Botev landed in 1876 with 200 volunteers, having hijacked an Austrian steamer, in an abortive attempt to suppоrt the April Uprising. Today it is also the site of Bulgaria`s only nuclear power station. The next substantial town is Oriahovo (Оряхово), site of a medieval fortress destroyed by the Crusaders and perhaps best known now for its wine. Beyond Baikal, some 50 kms. further, where the River Iskur joins the Danube is the site of a Roman and then Byzantine fortress, Oescus. One of the biggest along the river, it boasted a bridge over the Danube, reputedly some 4000 ft. long, The fortress and the bridge were destroyed the Avars in the 6th century. Another 50 kms. further is the old Roman town of Nikopol (Никопол) overlooked from a crag by its fortress. Built in 169 by the Romans, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius strengthened it in 629 adding 26 towers. Tsar Ivan Shishman made it his unofficial capital during the Second Kingdom, naming it Basha Tabia Kale. In 1393 it fell to the Turks, prompting the Christian powers to institute a disastrous attack, plagued by disunity and internal dissent, on it in 1396.

From Nikopol the road takes a detour inland, bypassing the riverside town of Belene (Белене), famous only because of the katorga, labour camp, the communists established on Belene island opposite the town. Between 1947 and 1989 it housed political prisoners, opponents of the communist regime, many of whom disappeared during their incarceration. Today the island is a nature reserve, the Persina National Park, all traces of its previous occupants having been removed. At Svishtov (Свищов) the river reaches its narrowest point before the sea and as such the site has long been occupied (the name is said to come from the Bulgarian word for candle, referring to an old lighthouse there). The Romans built a port a little to the west of the present town, the remains of which can still be seen. Svishtov was also the birthplace of the satirist, Aleko Konstantinov, creator of Bai Ganyu (see Literature) and a museum house is dedicated to him on Ul. Klokotnitsa. The town has two churches by Kolyo Ficheto, Sv. Dimitur and Sv. Petur and Paul. From Svishtov the road follows the Yantra River inland to join the main E85 to Ruse.

RUSE (Русе)

`All culture flows down the Danube to Ruse`, as the town’s people are fond of saying and indeed, despite the inevitable blocks of flats and the industry surrounding the port, Ruse prides itself on a cultural life second only to Sofia’s. Older, certainly, Bulgaria’s first professional theatre performance was given here in 1871 and the town still has something of the feel of fin-de-siecle Central Europe about its older streets. It has a cosmopolitan air, too. As the historical arrival point of refugees fleeing pestilence or war down the ages, it has long been accustomed to absorbing different cultural influences. A tradition which continues today as Bulgaria`s major road link with Romania and hence the rest of Europe crosses the Danube over the bridge between Ruse and the Romanian port of Gurgui.

A LITTLE HISTORY....

A 5000 year old settlement mound provides evidence that there had been a small Thracian settlement on the site of the present town but the first major settlement was established by the Romans who built the port of Sexaginta Prista (Sixty Ships) here, probably established by Vespassian between 69-79AD. This lasted until the 6th and 7th centuries when, harassed by raids of Goths and Huns, its inhabitants moved 15 kms. inland to found the fortress of Cherven. In the middle ages Cherven became one of Bulgaria`s leading cultural centres, known as the `city of churches` and `the city of the Bulgarian bishops`. Razed to the ground by the Turks in the 14th century, understandably keen to destroy any potential source of Bulgarian dissent, what remained of its inhabitants moved back to the original riverside site. The Turks in turn fortified Ruse, known in Turkish as Ruschuk, and established it as a major naval base in 1603. By the 17th century it was, in effect, a Turkish town, of its 18,000 inhabitants, 15,000 were Turkish and a contemporary Turkish chronicler, Hadji Kalfa, wrote of it that it contained 6000 houses, public baths, many mosques, bazaars and a suspension bridge. Up until 1864, Ruse was essentially a fortress, albeit of such importance that the Russians tried often to capture it (succeeding briefly twice, in 1774 and again in 1812), but in that year its Turkish governor, Midhad Pasha, established it as the principal town of the Danube vilayet, inaugurated an educational system and built the Ruse-Varna railway line, Bulgaria’s first and a major trade corridor between Turkey and Western Europe. The effect of this latter was that Ruse became a principal port of call for travellers between Central Europe and Constantinople, many of whom settled in the town. As well it had become a centre for the liberation movement under two leading lights, Rakovski and Bulgaria’s leading woman revolutionary, Baba Tonka.

After the liberation Ruse was the largest town in the new state and the most prosperous. Many merchant families, Greeks, Germans and Armenians, settled here and the town began to take on the appearance of a prosperous Central European town. A burgeoning trade with Austria down the Danube made itself felt on the pattern of social life, Viennese cafes opened, an opera house was established and a rich society grew up, giving the town a stamp of elegance and luxury which lasted until the Second World War.

THE TOWN

Life in modern-day Ruse revolves around Pl. na Svobodata (Freedom Square) dominated by the 60 ft. high Liberation Monument. Built in 1908, the bas-reliefs show the battle of Buzludzha and the battle of Shipka Pass (see History). On one side of the square is the baroque facade of the Drama Theatre and the Opera House. The town`s main shopping street, Ul. Alexandrovska, crosses the square, the scene for the evening promenade that is the main feature of Ruse`s nightlife. The area around the square and between the square and the river was the heart of the 19th century town and is worth a stroll to see some of the grandiose merchants` houses. North of the square, Ul. Baba Tonka leads down to the waterfront and the Baba Tonka Museum-House which the redoubtable Baba (lit. grandmother) Tonka Obretenova turned into a centre of revolutionary activity. She sheltered patriots on the run, hid weapons, smuggled arms in from Romania and led an assault by the town woman on Ruse prison. Her five sons were all active in the liberation movement and the museum documents the family’s activities and also contains the effects of other revolutionaries including the skull of Stefan Karadzha which she preserved as a symbol of the movement. One of her daughters married Zahari Stoyanov whose museum house is close by on Bvd. Pridunavski, facing the river. Stoyanov was a journalist, author and activist whose best-known book, Notes on the Bulgarian Uprising, details the activities of Benkovski (see Koprivshtitsa) whose cheta he joined during the April Uprising. The museum is divided into three parts, one devoted to Stoyanov, another to Panaiot Hitov, a haiduk whose life in the mountains is detailed by exhibits of ancient pistols, tobacco pouches and other accoutrements of haiduk life and an exhibition of folk costumes from Ruse. Around the corner is Kaliopa House, a museum which explores Ruse’s role as the gateway to Europe.

South of Pl. na Svobodata on Ul. Sveti Gorazd is the Church of Sv. Troitsa (the Trinity). Dating from 1764 it is the oldest church in Ruse, built on the site of an older sunken church and is heavily influenced by Russian church architecture, particularly the spire. The nave has a display of icons.

On Blvd Slavianska, at the bottom of Alexandrovska, is the house of Bulgaria’s Nobel Prize winner for literature, Elias Canetti. Carry on down the street past the statue of Angel Kunchev, a Bulgarian freedom fighter who, rather than be captured by the Ottomans, shot himself at this spot, and you reach the old Roman fort of Sexaginta Prista.

If anything Ruse has a surfeit of parks, most of which are full of people in the summer evenings strolling or drinking coffee in the many cafes among the trees. Park na Vuzrozhdentsite is a short walk east from the church and contains the Ruse Pantheon, a monument to those who died during the struggle for liberation, including members of Baba Tonka`s family. North towards the river, Mladezhki Park (Park of Youth) has at its northern end a Transport Museum (open every day), celebrating Midhat Pasha`s railway with locomotives and rolling stock from the period.

There is no shortage of eating places in Ruse, the majority of which are on or around Pl. na Svobodata, ranging from the up-market restaurant in the Hotel Riga to cheap and cheerful open-air cafes around the square. The town’s most unusual and popular restaurant is the Leventa restaurant on the site of the old Turkish fort a little out of town (bus 18 from the railway station). Each of its seven rooms serves food from different countries bordering the Danube.

AROUND RUSE

South of Ruse the Rusenski Lom river has cut an impressive gorge out of the surrounding countryside. The gorge, now a national park, provided an excellent defensive position for those seeking security in insecure times and thus there are a number of fortress and monastical ruins around its walls. The two most accessible are the Monastery at Ivanovo and the ruined Cherven fortress. The Rock Monastery near the village of Ivanovo (Иваново - bus or train from Ruse), dating from the 13th and 14th centuries, is cut into the 160 feet high gorge walls, Established by Joahim of Turnovo, the monks came to this place to live the life of ascetics away from the wordly pleasures of nearby Turnovo and Cherven. The complex consists of cells, galleries and churches either cut from the limestone walls or built into existing caves which were then whitewashed and decorated with frescoes. The Tsirkva (church) cave has unusually realistic frescoes of biblical scenes. Two in particular stand out. The Washing of the Feet has an intense vitality and the unknown artist had a sophisticated grasp of composition, all the figures are arranged in a geometrical pattern of triangles and semicircles. The figures in the Betrayal of Judas are muscular and lifelike demonstrating a mastery of form unmatched in contemporary frescoes elsewhere. The Cherven fort (Червен Крепост) complex (train to the village of Dve Mogili – Две Могили and bus thereafter to the village of Cherven) perches high above a fork in the river surrounded on three sides by cliffs. The site was sporadically occupied until the 17th century although much of it was destroyed earlier by the Turks. The extent of the ruins that remain today are sufficient to show the size and sophistication of the original fortress which was one of the primary military and administrative centres of the Second Kingdom and at its height exceeded 1 square kilometre.

Lipnik Forest Park, 10 kilometres east of Ruse near the village of Nikolovo (bus from Ruse), is a popular weekend destination for the town`s citizens. Much of the park is dense forest with a well-laid network of paths and a hotel and restaurant complex.

SILISTRA (Силистра) AND SREBURNA LAKE (Сребърна езеро)

Silistra, the last Bulgarian town on the Danube, would in itself, apart from a Roman tomb, be of little interest to the visitor were it not for the proximity of the nature reserve at Sreburna some 12 kms. west of the town. The lake is on a UNESCO list of world valued sites and its reeds and rush islands are nesting sites for almost 90 varieties of birds, many rare, and a stopping off point for as many migrants including in autumn, egrets and pelicans.

Silistra`s town square has a pleasant 16th century mosque on one side and the Archaeological Museum with many Roman remains on display on the other. East of the square Roman ruins abound. South of the square Ul. Vasil Kolarov leads to the Roman Tomb, a 4th century edifice with many well-preserved wall paintings of the interred couple. Silistra can be reached by bus from Ruse or the Varna train from Ruse and change at Samuil.

Driving south from Silistra along route 7, it is worth taking a detour to Sveshtari (Свещари) and the Sboryanovo archaeological complex (on the road between Sveshtari and the neighbouring village of Maluk Povorets). A UNESCO World Heritage Site, it is the site of Helis, the capital of the Thracian Geti tribe in the 4th century BCE. The most well-preserved remains on the site are those of a Thracian tomb with spectacular stone frescoes. The largest and oldest of the remains is that of Kamen Rid, a walled religious sanctuary which dates back to the Stone Age. The surrounding area is home to a Muslim sect called the Alevi, and a 17th century Alevi tomb, the Demir Baba Teke, built on an earlier Thracian religious site, is also part of the reserve.